What issues do his albums raise in terms of representation of ‘race’, and particularly ethnic and cultural stereotyping?

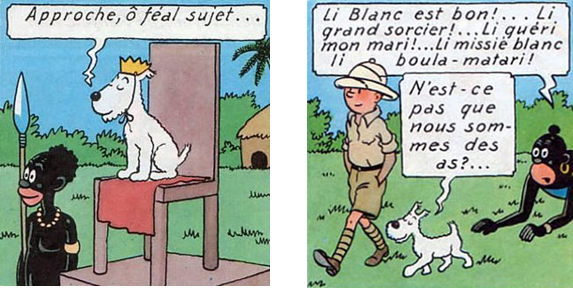

If the term ‘aged like milk’ has any accuracy, then the flavour of the older Tintin albums is at times remarkably sour. Over the long course of the series Hergé has built an impressive roster of cultural stereotypes that have been the cause of criticism in modern days. The first example appeared in the very first volume Land of the soviets where the Chinese are depicted with eyes so slanted, they are literally just lines on their faces, with pig tale haircuts that are about to torture Tintin. Arguably the most outrageous case comes in the second volume Tintin in the Congo. In this volume, African people are depicted with comically oversized rounded lips that are a bright red in colored versions, large eyes relative to other characters, speaking in broken english, wearing western clothing incorrectly, and having low intelligence. Tintin educates the natives about Belgium, a reference to the ‘Belgian Congo’, the Belgian colonial exploits of Congo, in which the natives were exploited and exposed to violence, while also given little in the way of healthcare and education. As Hergé explains it, The inclusion of this in the comic was meant to be a reflection of his paternalistic feelings in regard to the colony. This is the first example of Hergé’s misguided attempts at including race in his work. Not only is the profile of the natives in the comic highly stereotypical and degrading, but Tintin is also in the unfortunate role of the white man that fixes their problems and becomes their ‘master’. A year later in Cigars of the Pharaohs the artistic depictions of Africans still remain consistent. Hergé’s depiction of native Americans was a slight improvement, with the primary goal of his third entry Tintin in America being intended as a critique of American capitalism and treatment of Native Americans. The Native Americans in the comic are written to be sympathetic, but Hergé still depicts them as gullible and naive, as well as less intelligent than the white characters. With the fifth volume The Blue Lotus the visual depictions of the Chinese characters have toned down from their depictions in Land of the Soviets which may be due to the fact that Hergé’s view of the Chinese in this story was sympathetic unlike in Land of the soviets. This maybe explains why his depiction of the Japanese antagonistic force in The Blue Lotus was more questionable, with his visual depiction of the character Mitsuhirato being suspiciously similar to anti Japanese war propaganda. Whether Hergé chooses to view other races in a paternalistic or sympathetic manner, their depictions still are more often than not problematic. I do believe that Hergé is not a racist and that the messaging of his work is well meaning, but ultimately misguided in execution. This is best illustrated by Tintin himself, who educates the Congolese and solves their problems, because they need him to. Who nearly gets killed by Native Americans that were easily tricked and imposed on by the ‘bad whites’. Who saves a drowning Chinese boy, and treats him as someone he needs to protect. Hergé’s paternalistic and sympathetic views on other races resulted in depictions of these races that required a smart competent white man to help them, and that is why the early volumes have aged like milk all these years later.

Mountfort, Paul. (2011). Yellow skin, black hair … Careful, Tintin’: Hergé and Orientalism. Australasian Journal of Popular Culture 1(1), 33-49. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajpc.1.1.33_1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintin_in_America

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blue_Lotus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintin_in_the_Land_of_the_Soviets