How and why have Tintin’s gender and sexuality been questioned?

No artist, dead or alive, has full control over how their work is interpreted. For Hergé this must’ve been an inconvenient reality, as the likely intentional lack of solid defining traits for Tintin as a character would backfire in the long run. It was to Hergé’s disgust after all, when people began to question Tintin in ways that Hergé would have never predicted.

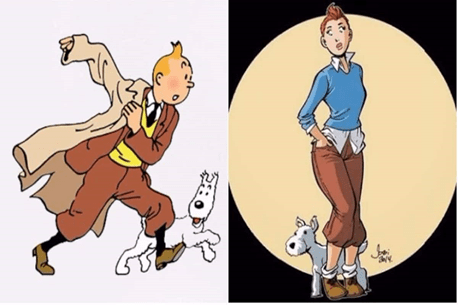

The first aspect of Tintin that has been brought to question is his gender. In terms of personality traits, Tintin doesn’t seem to strongly lean either way, for a character that exists within a ‘boys world’ he is surprisingly lacking in masculine traits. Furthermore, when in relation to Captain Haddock, Tintin begins to adopt feminine traits like being observant, silent, and tender. Tintin has the physical attributes of a teenager, despite almost certainly seeming to be an adult, since he provides for himself and is mostly independent, we never see even a strand of hair on his face or chest, and we have certainly never seen his genitals. The evidence that Tintin is a girl isn’t exactly substantial, and yet the same can be said for him being a guy. For a world that was designed to be for boys, that girls don’t belong in, Tintin doesn’t seem to entirely fit into that, and that is suspicious. The implications are that Tintin is a tomboy, rather than a real one, which may have some logic behind it. If I were a female journalist traveling the world in the time period of Tintin, I imagine I might dress as a boy to avoid prejudice.

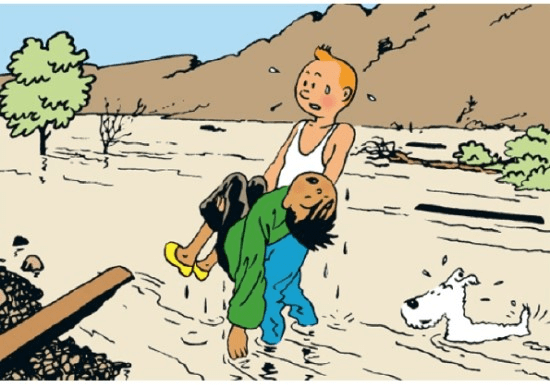

The second aspect of Tintin that is in question is sexuality. Not once does Tintin show any kind of sexual or romantic desire towards anyone, which leaves it up to the reader to speculate. The lack of any kind of carnal desire from Tintin would immediately suggest that perhaps he is asexual, but there is still another option. All of Tintin’s strongest relationships are with men. As I mentioned before, Tintin’s personality had a slight change after he met Captain Haddock, and the two of them sometimes live together. There is also the strange scene where Haddock attempts to uncork Tintin, some saying this is Haddock symbolically penetrating and screwing Tintin. The character that Tintin seems to emotionally care about the most is Chang. Tintin dreams of Chang, cries out his name in waking, and weeps for Chang (Mountfort, 2020.)

Ultimately the actual arguments for Tintin being a girl or being gay or asexual are not particularly convincing, but it is equally impossible to prove that Tintin is a heterosexual male. The reason that these aspects of Tintin are questioned so intensely then, is because Tintin, by complete accident it seems, is an unidentifiable unknown, a puzzle with no intended solution.

Mountfort, P. (2020). Tintin, gender and desire. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2020.1729829